On Sunday the 10th of October, I committed the final outrage against my family. I spoke the eulogy at my Mother’s funeral. The family will never speak to me again. I can handle that.

When I say “my family,” I mean, mostly, my Mother’s side. The Rosenthals. Who resemble in more ways than the mind can readily support, the brutalizing members of the Sproul clan in Jerrold Mundis’s current and brilliant novel, GERHARDT’S CHILDREN. They remind me of the first line from Tolstoy’s ANNA KARENINA: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

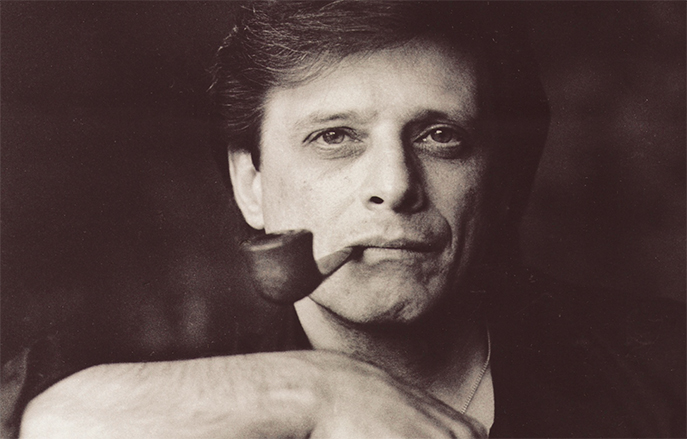

And prime among that unhappy family’s myths was the one that Harlan, Serita and Doc’s kid, Beverly’s brother, would wind up either dead in an alley somewhere, having come to a useless end … or rotting away his old age in a federal penitentiary. That I became a writer of some repute and became the first member of either the Rosenthal or the Ellison family to get listed in WHO’S WHO IN AMERICA, confounds them to this day. To them, I am like the snail known as the chambered nautilus, that has a shell with rooms in it. As the nautilus lives its brief life it moves from room to room in its shell and finally emerges and dies; thus, it literally carries its past on its back. To the family, I am still a nine-year-old hellion who took a hammer to Uncle Morrie’s piano. (The fact that this never happened, that Morrie never owned a piano, does not in any way invalidate for them the essence, the canonical truth of the legend.)

It is probably no different for anyone reading these words. All families form their opinions of the children early, and so we spend the rest of our lives in large part paying obeisance to shadows who neither care nor in fact have any power over our reality. It is thus for all of us, no matter how sophisticated and cut-loose we may be from the familial spiderweb.

To them, I am a nine-year-old chambered nautilus; even though I ran away from home at the age of thirteen, grew up, and have barely spoken a dozen words to my sister in the past ten years.

But there was still my Mother, whom I supported in large part during the last years of her life, picking up the burden, when I was financially able, from my Uncle Lew and my Uncle Morrie and from Beverly’s husband, Jerold.

My Mother had been terribly ill for many years. To my way of thinking, she wanted to die on May 1st, 1949, when my Father had his coronary thrombosis and died in front of both of us. He was her life, her happier aspect, and she became—in any sensible not even exquisite sense—almost somnambulistic.

In August she had the latest of an uncountable number of strokes, followed it with a full-sized heart attack, and was taken into the Miami Heart Institute. She knew the end was on her and she let me know that was the sum of it when we talked long distance.

She lay there getting worse and worse, and finally, forty-five days before the green blips went to a flat line on the monitor, she was down from one hundred and twenty pounds to forty-one pounds, her lungs were filled with fluid, her brain had swollen so her face was terribly twisted, her leg was filled with blood clots, her blood sugar had risen to an impossible level, she ran a temperature in excess of 102° constantly, she was blind, paralyzed, and no oxygen was going to the brain.

Blessedly, she was in deep coma.

She never recovered consciousness. They kept her on the IV and the monitoring for a month and a half. She was a vegetable and had she ever come out of it would have been an empty shell. I begged them to pull the plug, but they wouldn’t.

The greatest fear my Mother ever had was that some day she would wind up

in a nursing home. She thought of them as hellholes, as repositories for discarded loved ones, as the very apotheosis of rejection. She begged us never to put her there.

Shortly before she died, the Miami Heart Institute held one of their “status meetings” and decided she was “stable,” that is, she needed custodial care. And so they wanted her out. They suggested we get her booked into an old folks’ home. They used another phrase. They always do. But it was a hellhole, an old folks’ home.

Beverly, my sister, who had gone through the anguish of the last six weeks down there, was forced reluctantly to find such a place. On Friday, October 8th, 1976, the day my Mother was to be removed from Miami Heart and carted by ambulance to the hellhole, though she was in deep coma and could not possibly have known what was intended for her dead but still-breathing husk, she chose to expire at 5:15 a.m.

In some arcane way, I’m sure she knew.

When my brother-in-law Jerold called to tell me Beverly had just advised him of Mom’s death, he asked if there were any arrangements I particularly wanted. “Only two,” I said. “Closed casket, and I want to read the eulogy.”

From that moment till Sunday at the funeral services, my family trembled in fear of what I would say. They knew I was no great lover of the clan, and they were terrified I would make a scene, depart from protocol in a way that would humiliate them in front of friends and relatives. They gave very little thought to my feelings about my Mother. But that’s the way it always is, I’m sure, with all families, with all deaths.

I flew all night Saturday and got into Cleveland (where my Mother’s body had been taken, so she could be buried beside my Father) at 6:30 in the morning. I drove to Beverly and Jerold’s house and when Jerold asked to see the eulogy I’d written, which was almost the first thing he said to me, thus indicating the obsessiveness of their concern about “crazy” Harlan and what he might do, I lied and said I hadn’t written anything, that it was to be extemporaneous, from the heart.

The relatives began arriving, and with the exception of my Uncle Lew, who has always been the coolest and the most understanding of the clan, they all circled me warily as if I were a jackal that might at any moment leap for their throats.

At the funeral home, Rabbi Rosenthal seemed equally uneasy about my participation in the ceremonies. It was Succoth, the Jewish harvest holiday, and just a week after Yom Kippur, the holiest of the holies. Thus, certain prayers that are usually spoken at funeral services could not be spoken; alternate words were permissible, but few, so very few.

Rabbi Rosenthal is no relation to my family. His name and my mother’s maiden name being Rosenthal is just coincidence. Like Smith. Or Jones. Or Hayakawa. Or Goetz. Or Piazza. He’s a fine man, the Rabbi Emeritus of Cleveland Jewry, a strong and familiar voice in Cleveland Heights and environs. He has been for many years. But he didn’t know my Mother.

My family felt themselves honored to have pulled off the coup of Rabbi Rosenthal attending to the services. My family thinks in those terms: what looks good … social coups … fine form and attention to protocol. As you may have gathered, I am not concerned with shadow, merely reality.

Nonetheless, he advised me he would speak the opening words and then would call on me.

Before the main room with the pink anodized aluminum casket was opened to the attendees, the immediate family mourners and their spouses and children and grandchildren were taken to a family sitting room to the right of the main chamber. Jane Bubis, Beverly’s best friend, bustled around. Morrie met old chums from Cleveland. My nephew Loren and I insisted on seeing Mom.

Everyone told us not to look, that she had withered terribly, that we should “remember her as she had been.” They always tell you to “remember” someone as “they were.” Bear that phrase in mind. The nature of the outrage I committed against my family is contained in my pursuit of that admonition.

Loren and I insisted.

It didn’t look like my Mother. It was a cleverly constructed mannequin intended for some minor wax museum in an amusement park. The embalmers and cosmeticians had done as good a job as could be done, I’m sure; but it wasn’t my Mom. She was already gone. This was a stranger. But I cried. Pain that clotted my chest and made me gasp for breath. But it wasn’t my Mom.

The service began, and when Rabbi Rosenthal called on me, I walked up to the lectern, trailing my hand across the casket foolishly to establish some last rapport with her.

I pulled the pages I’d written from my inside jacket pocket and though there was no appreciable movement in the people sitting in front of me in the main chamber, the agitation I caught with peripheral vision, from the family seated in the side viewing room, was considerable: the frenzied trembling of small fish perceiving a predator in their pool.

Understand something: my sister and I have never been friends. Eight years older than I, she was always distressed at who I was, what I was, what I did. (I have long harbored the fantasy that I was actually a gypsy baby, stolen from the Romany caravan by an attacking horde of Jewish ladies with shopping bags.) Beverly is no doubt an estimable human being, filled to the brimming with love and charity and compassion. I have never been able to discern these qualities in her, but she has many loyal friends and if an election were to be held among the relatives, as to which of us could safely be taken into polite society of an evening without worry about a “scene,” my sister Beverly would win in a walk. Though they take a (to me) somewhat hypocritical pride in my achievements and the low level of fame I’ve achieved for the Ellison family, it is a public pride, not to be confused with actually having to get near me. I can handle that, too.

As I began to read, my sister began to fall apart. I’m not sure if it was the “inappropriateness” (to her mind) of what I was saying, or the fact that I was crying and having difficulty reading the words, or that the torture she had undergone for six weeks had finally broken her, but she began writhing in Jerold’s grasp, and in a voice that could be heard throughout the funeral home hoarsely cried for Jerold to “make him stop, make him stop! Stop him!” Beside her, her daughter, Lisa, my niece, snarled, “Shut up, Mother!” but Beverly never heard her. She was manipulating her environment, and her lunatic brother Harlan was doing another of his disgusting numbers, desecrating the funeral of her Mother. They finally manhandled her into another room, where her cries could still be heard. And I went on, with difficulty.