His relatively new face was clammy with sweat. Somewhere in front of him Lederman was crouching, a ripper poised, waiting to shoot him down. He made a feeble movement with his gloved hand, toward the sweat of his face, and realized before the motion was completed that he was still bubbled.

He sank back behind the rock, rubbing his shoulders against the ebony basalt, getting faint relief through the spacesuit for the rivers of perspiration that raced to the small of his back.

Emory bent his head inside the bubble helmet to the sip-tip protruding from the inner circle of his sealing collar, and sucked deeply. It was warm now, but good. After thirteen hours of sparring with Lederman, any sort of relief was welcome.

He tipped his ear against the transparent plasteel of the bubble helmet, laying the bubble against the enormous rock. He held his breath, struggling to catch the sound of movement, conducted through the stone. Nothing. Lederman was silent, waiting, wherever he was.

A sudden, inexplicable terror rose in Emory, and he sprang away from the huge boulder, throwing himself onto his back, the lektroknife blade upward to thrust; he stared up into the black, airless sky of the asteroid. The crest of the boulder was framed against the sullen stars, but no dark shape of a man crouched there.

He was starting to crack, and he knew it. Thirteen hours…hell, thirteen years and two more…had taken their toll. His flesh was wet, his mind a turmoil. And worst of all, he was afraid.

It had taken Emory far too long to realize he was a coward; for it to appeal to him. It had been slow in coming, as it is always slow in coming to men who live in self-styled worlds of bravado and delusion; often he had told himself he would react in the heroic fashion to the proper stimuli, the excitement of the moment.

But time after time, when the chips had been laid out, he had found himself balking, fearing, and most disgraceful of all—running. He no longer had any illusions about himself. It had been long in coming, but now he knew: he was a coward and there was no other way for him to die.

But here, on this asteroid Lederman had named Brutus, he would die in his own way, in his own time, taking Lederman with him. Lederman had been the only thing that had kept him going those fifteen years and thirteen hours—the hate of Lederman. The all consuming, ripe, building fire of loathing that had motivated him across a galaxy, and here to this isolated, wasted rock in space.

The thing that had changed his life twice, his face once, and his soul eternally.

Lederman would die; as sworn before god, Lederman would die on this rock. He crawled back to the shelter of the boulder, and sat down once more.

The air regulator on his chest console clucked inside the bubble, and he glanced down apprehensively. Yes, that followed. The air was getting stale. He would not run out, but what was being recirculated back to him from the moss-sac was so rotten and rancid, he might vomit inside the bubble, and have to live with the odor and swill for god knew how long. He bit his full lower lip.

And a vagary of light from the stars caught the bubble, casting back the reflection of Cal Emory.

There was nothing handsome about him. His face was too wide, and his skin too dark. His hair was almost blue-black, and it ran down the back of his neck, into thick growths of side-burn, tumbled over his forehead in an uncontrollable, wild mass. His great dark eyes—flecked with some unnameable color—looked out from under the thick mat of hair. But not even in the eyes was there beauty. Destruction. Vengeance. Darkness. But nothing of beauty.

He saw, in that instant of star reflection, the hard lines that came down from either side of his nose, to the corners of his mouth. Scowl lines, beaten into the flesh by years of drawing down the full lips.

Again he tried to wipe his mouth with his hand, and found himself locked from the movement within the twin casings of bubble and mitten.

He laid his head against the great black rock. It was such an empty place to duel, this Brutus, swimming unconcernedly in the night sky. Such a dead place to live, to die, to do anything. He felt a surging unhappiness overcome him as he realized how inevitably dreary it was that this should be the final arena of decision.

How like this rock in space his life had turned out to be. How desolate, and wonderless, and wandering, with its towering basalt mountains, its deceptive craters and sinkholes, its featureless plains.

Brutus lay in the palm of space like a lump of coal. Empty. Dead. They were alike.

The scrape or something over rock came to him through the boulder and his bubble.

Sweat that had retreated momentarily while his thoughts wandered more coolly, now returned with force, and he licked his suddenly chapped and dry lips, bringing the lektroknife up before his strained face. The starlight caught the blade, and he dipped it quickly; its glow would give him away. The scraping came again.

He flattened himself against the boulder, crouching with the strength of his thigh and calf muscles. His face twisted in strain, his hand tightened about the weapon.

Not much of a weapon against a ripbeam, but all he had—now that he’d lost his own handgun. The sound of movement seemed to be advancing over the crest of the boulder.

He thought he detected the clank and tinkle of metal, but that might have been his imagination. He couldn’t worry the thought; the next instant a shape rose over the hump of the boulder, and he sprang upward violently, a scream tearing from between his lips.

With negligible gravity on the asteroid, his spring carried him up and up and up, driven with terrific momentum, till his body cleared the rock’s spine, and his arm shot up, ripping at the flesh of the shape moving toward him.

The lektroknife blurred with its glow in movement, and its aura deepened as he poured power to it from the handle. The weapon entered the body, slick as grease, and was withdrawn as quickly, having pierced to nerve centers, having spread its billion tendril-killers in the split instant of contact, having radiated deadly current through the body…enough to kill a thousand men.

He felt himself falling, and he landed at the foot of the rock, his knees bent, as the body crashed down before him.

Only then did he realize the dark shape was not Lederman, but the body of a rock-crawdad, one of the peculiar insect-like creatures that inhabited Brutus. He stared at the huge, veined sac hanging beneath the creature’s neck, into which the rock-crawdad sucked air from the hidden pockets deep inside the asteroid.

He stared at the creature, and knew he was getting too nervous to hold out much longer.

Somewhere out there, armed with a ripper, was Lederman. Waiting for the chance to skulk in here and saw off the top of Emory’s head with the ripbeam.

Perhaps this had been the slip.

Perhaps Lederman had found the rock-crawdad and sent it over the rock to belie Emory’s position.

As if in answer to the mute wondering, a thick, golden beam of energy sizzled silently out of the darkness, and spat itself against the boulder over Emory’s head.

The rock sheared away, leaving a bright smear, and Emory took a forward somersault, tumbling frantically away from the boulder that was now a death trap. He scrabbled away in the eternal darkness, and after a long time found a shallow depression beneath another huge boulder, into which he sank.

Now was not yet the time. He had to wait it out.

Lederman was still more potently armed. But the time would come; the odds had to change. They had to. Fifteen years he had waited; he was not going to be cheated of his prize now.

He settled more comfortably into the depression, turned his air a trifle lower, conserving it, and waited.

Time passed, and memory thoughts climbed in swirling patterns.

Chapter One

At first it had been friendship. Loneliness breeds attraction, and Cal Emory was a lonely young man. The Institute for Spatio-Geology was a big school, almost as big as Rutgers School of Speleospatics; but he had been unable to gain admission to Rutgers, chiefly because he was unable to raise the exorbitant fees.

On the other hand, R.P. Lederman had more money than he had ways of dispensing it, yet his son was deprived the Rutgers admission, also. The reason was greatly different from the one that had kept Emory out; it was a matter of reputation, and a scandal in New Washington involving rare floss-gems from Io and the drive-tub liners for government vessels. R.F. Lederman, Sr., had been featured on the cover of Timeweek and the article about him had not been laudatory.

And so, because both were from New Washington, and because both were young and not “in it,” Lederman, Jr., and Emory became friends.

They arranged their schedules at ISG to coincide; they double-dated; they visited each other during the vacations, and grew to like one another.

Then, as so often happens, there was a girl. Her name was Dorothy, and she was that peculiar blend of good looks and sharp wits that could attract two such different young men.

Emory met her, and spent a great deal of time with her. But he was unable to hold the line against Paul Lederman’s continental ways, and all-too-sincere show of wealth; for Lederman knew ostentation was the surest way of losing such a girl. So he plied her in a way that made his money and position seem unimportant to him. She responded gratifyingly, and they were married in Lederman’s junior year at the Institute.

It was, of course, the shearing of Emory’s friendship with the other. But though it planted the seeds of hatred, they were not to spring into full blossom for some time, despite Emory’s backing-down where Dorothy had been concerned. That had been the first concrete evidence Emory had had, that his will was not strong. He had allowed himself to be pushed out of the picture rather than assert himself aggressively.

Lederman never lorded it over him; that would have been out of character, not at all the thing a man with class would do. But there were frequent invitations to dinner at Lederman’s newly-decorated off-campus apartment, and Dorothy looked too radiant for the bitter memory ever to fade.

In their senior year, there was a scandal in the class. Sample cases for the final exam had been switched. Cal Emory was accused of having caused the substitution, for the case he submitted was notched as belonging to one of the previous classes, the property of a high-ranking student from the year before.

He was expelled, and with his expulsion came a friendly offer from Paul Lederman to work for Lederman Intergalactic, as a geological consultant. The pay was not great, but it was a job, and Emory took it without too much thought of the consequences. Yet thoughts of how his own sample case had been switched did plague him; though he never reached a satisfactory conclusion. It was a black mark, and one he could not erase. And the dislike grew slowly.

It grew in intensity, to the point of taking on full form and identification, when Lederman graduated, and moved into second slot in the Lederman Intergalactic organization. Then Emory’s job grew distasteful; he found himself being sent out on Skulkships to route the ore diggers from worthy asteroid to rich planet. He was kept off-Earth more than landside.

But it was a steady job, and the pay had grown, so he swallowed the bitter phlegm of Lederman’s actions, and reconciled himself to saving his money till the day be could break away and form his own outfit.

Then, nine years after the first day he had met Paul Lederman—now R. P. Lederman, Jr., and sole head of Lederman Intergalactic with the heart attack death of his father—Dorothy died.

Not cleanly, but in an institution, prey to weird grey delusions, and mouthing imprecations against her husband and his tarts, the agony of her life with him, and the horror of the way their baby had died.

Paul Lederman had not wanted children; the baby had been handled in the incubator rooms. She had never seen it, indeed would not have known it was murdered, had not an acquaintance been Nurse-On-Duty at the time, and confided the truth later.

It was a marriage of five years. Five years that had altered Dorothy so greatly, that despite the magics of the embalmers and the plasteks, Emory was hard-pressed to recognize in that carcass the gems of beauty and wit he had loved when first they had met.

Ironically, he was landside when it happened. Had it been two weeks either way, he would have been blasting, and would have missed the funeral.

Emory did not miss the funeral, but Paul Lederman did. The ceremony was a simple affair, paid for out of Lederman Intergalactic’s petty cash fund.

She hung there, two feet above the dais, on her pneumopad of rich, purple velvet, hands folded across her breasts, the fingers delicately arranged to connote peace. But there was no peace in the lines of her face, showing through the plastwork and grease paint.

The professional mourners were arrayed on risers, in a neat pyramid on the dais behind the pneumopad, and their wailing was done in depth and harmony. Theremin and sackbut music—and was that the faintest tremble of a lyre?—hovered vaguely in the air of the Necrodome, pitched to subliminally catch the mood the Arrangers had desired.

It was lovely, and Emory was heartsick, knowing it was lovely because they had wanted it to be lovely.

He fell in behind the paid Respectables who filed up the escalator and across the dais to the pneumopad. In front of him a short, swarthy man with a gigantic cheek mole looking like a pitch spot on his dark flesh was pinching his fingers together in the traditional sign of sorrow. The little man stopped and a catch in his throat was so evocative of misery, that Emory felt his nerves tighten, his anger roar into flaming life. He could never know what made him do it…but the falseness of it, hiring Respectables, the sham and mummery of it all! This slime before him, feigning sorrow at six dollars and eighty cents an hour.

He saw his hand reach out and wrap in the little man’s tunic bat-wing collar. He saw his arm jerk the little man around, and grip him by the throat. He saw his other hand go between the little man’s legs, and then he was lifting the Respectable over his head by neck and crotch.

He was still unaware of what he was doing, as he threw his back into it and hurled the little man bodily from him. The Respectable went spinning in a welter of arms and legs, his short tunic flopping up to cover his head. He landed with a sickening whump! in the center of a still-growing floral display that withered and turned black as he crushed it.

Then Emory turned to the pneumopad.

The other Respectables had fled in terror, and he sank to his knees beside the royal purple lining. His hand came out to touch the artificially warm flesh of the corpse, and there was an unspoken promise on his lips.

He drew back the hand, and saw that he had left finger whitening on the flesh. Then the keepers of the peace stole silently up behind him, grasped him firmly under the armpits, and despite his height, lifted him forcibly from the dais. He was carried out of the Necrodome, and thrown into the slidewalk gutter. It did not bother him; he had made his promise to the dead. Now there was only to fulfill that promise, and his life had been led.

It took nerve, and he had no nerve then, so he went to get some.

The place was called Budweiser’s New Washington, one of the identical little saloons in the Budweiser chain. He knew his way around them as he knew his way around every carbon copy restaurant in the Johnson’s-Schrafft chain, every tri-di house in the Desilu combine, or every house in the Les Soeurs Gabor string.

The string quartet was a Detroit-manufactured Muzak android foursome, and though they leaned heavily on show tunes and popera, they kept to the background, and it was what Emory needed most.

He slid into one of the soundead cubicles and dialed in for an Occasional. It came up through the tabletop a trio of minutes later, and Emory inserted his credit card into the slot. The ident chimed and the cage opened, allowing him to remove his drink. The cage sucked back into the table and was gone.

He kneaded his forehead, and allowed the soothing colors and sparkles of the walls to lull his thoughts. Not to deaden them: what he wanted now was fire, not ashes. But he allowed himself to drowse into a calm kill, with nerves tight and mind set.

After the third Occasional, he felt he could do it.

The android string quartet had left the popera swill and for some minutes had been doing what seemed to be contemporary harmonic explorations of a familiar sort. Emory had to strain to make it out, but when he recognized it, he was pleased. It was Les Sauvages by Rameau, concisely converted from the keyboard to strings, with hardly any chrome and polish added. As always, when he heard Rameau, he was amazed at how modern the 18th century master’s work could sound; no matter in what era it was played.

It took him a sharp instant to realize the soothing tonal configurations of the music had deadened his resolve.

He dialed a double Occasional, and when it came, he released it almost viciously. Downing it fast, he felt the lancets of fire spread across his chest and through his stomach.

He was almost ready.

When the flames had begun to crackle crimsonly in his head, he got up to leave. He had to get a weapon. No…it would be more appropriate to do it by hand. He left the bar.

The string quartet was doing the Weill-Gershwin My Ship from some obscure Old Broadway production.

Outside the bar, Emory stopped at the edge of the slidewalk. He did not want the fury to abate. Sliding would take too long, allow the liquor and hatred in him to cool. He put the small fingers of each hand in the corners of his mouth and let out a piercing whistle.

A flit skimmed down from the maelstrom of traffic above and settled an inch above the slidewalk before him.

He slipped in and the flitman gum-chewed over his shoulder, “Where to, Jack?”

“The Lederman Building. Fiftieth floor.”

The flit took off, straight up, and when they had climbed over truck traffic and commuter ranges, the flitman asked absently, “They got a deck?”

“Yeah. You’ll spot the beacon, it’s a blue and orange with the staggers in black. You can let me off right at the pad.”

The flitman grunted acknowledgment and tended to his driving, as a good flitter should. As the miles whipped by below, Emory allowed his promise to rise up in him, like oil in a derrick, building, building, but capping it at the last instant, only to allow its release when the right time came.

The night time was coming soon.

The hatred was boiling up in clear, undiluted form. This was the second time his life had been changed; he had not realized it the first time his life had been altered by that hatred—for then the loathing of Lederman had been subliminal. That had been the occasion of his being forced out of college and into servitude to the wealthy young Lederman. As if he had suddenly realized what a dolt he had been, he knew who had been responsible for his expulsion. But why? What twisted factor in Paul Lederman’s makeup had impelled him to do such a thing? Whatever it was, it had also killed Dorothy, and Emory realized fully, for the first time in his life, how lonely he had been—by his own desire—and how he had come closer to being not lonely with Dorothy than he ever had.

Lederman had taken that from him. Had taken Dorothy and what might have been, had taken his career, and now had taken his incentive to go on living to produce. All that remained was desire. A desire to have revenge.

His life had been changed once, subliminally. But this…this was the second time…the time that counted.

Now he knew who his enemy was, and he had begun to fight him.

Lederman had moulded him somewhat; he had shoved him onto the Skulkships, and tried to keep him there. Now Emory knew he would never have gotten off them, till the day they carried him Earthside and into the hole.

But all that was ended now. As suddenly as a short-circuit. It was ended, and there was something to replace it.

Hate!

“We’re here,” the flitman said, and they were.

The flit dropped down suddenly, giving Emory a bad moment with his stomach, and then they hit pad. He noted this was not a Greyhound flit, but a private one, and did not use his credit card. He counted out the fare and passed it across. The flitman grunted thanks for the tip.

Emory was there now, with company: the hate.

Interlogue Two: The Dream

Brutus lay sleeping under him. Hanging black as a spot of pitch in a sea of ebony, Brutus was—and was nothing more.

Emory felt the vibrations of space around him.

I’m going crazy, he told himself, with undeniable truth.

His face was turned to the stars, and through the bubble he could see all of space and eternity laid out in a panoply of greatness, out and out and unfolding in a Persian carpet of magnificence, all for him, only for him, for him alone. He yawned. How the ordinary intermingled with the uncommon, to make life bearable. How the stars merged with the yawns in a rightness so deep and pellucid he could but only marvel at his perceptivity. How the walking merged with the interspace drive; the eating with the telepathy; the glass with the plasteel. It was a cosmic plan, a god-devised oneness that made everything equal and proper.

How hate and love were one.

How sighs and cries were one.

How disease and despair and desire and decree, all ate at one another’s bowels. How it all was one.

And he slept.

After thirteen hours and more, he slept, and the dream came back in crystal detail, shored up by sense and scent, by rhyme and rhythm. The early evening he had found out why: the dream…and…

He remembered what the ante-room had been like. So clearly. The walls of a dark blue hue, with gold molding across the ceiling and in heavy rectangular sections at the center of each wall. Modern-framed paintings by Klee, Miro, Kandinsky and other Classicists hung low above the backs of two sofas, constructed not for comfort, but for keeping the sitters thereon attentive.

Ash incinerators stood close at hand by the sofas and the three uncomfortable Algerian Modern chairs.

A vid-plate, thirty inches and opaque, was set into one wall, and as Emory had passed through the entrance iris, the plate had smeared itself with color, quickly jelling into the impressive face of an Inner Secretary.

“Yes?” she inquired, an imperious tone in her controlled, slightly husky voice. Her face was oval, set off to advantage by her dark hair, pulled to one side and fastened above the right ear with a casmyte clasp that had rhinestone rivets as decorations. Her eyes were as dark as her hair, and she used them well.

“I want to see Paul Lederman.”

“You have an appointment, sir?” The mere thought of his having an appointment was made ludicrous by her tone.

“No.”

“Then I’m sorry, sir, Mr. Lederman is—”

“Tell him Cal Emory is here.”

“I’m sorry, sir, I can’t—”

“Tell him!” The forcefulness of his demand had startled Emory as it had startled the Inner Secretary, for her dark eyes widened momentarily, and a line of annoyance creased between her brows.

The picture squished and was gone. The plate was dead.

Emory walked around the room twice, kicking absently at the legs of the Algerian Modern chairs. He silently commanded Lederman not to refuse him an interview. He had to see him, now, before the fury died. He wished he had taken up smoking, so he could drop the lit butt on the white pile rug, dedicated with a twist of his foot—to Lederman’s image-in-his-mind; he was here for destruction.

His hands ached.

He turned to the wall, and stared at the Three Musicians of Picasso. He had always liked that painting; it was a pity Lederman had it in his office. He consoled himself with the knowledge that an interior decorator had put it there, that indeed, Lederman had probably never even noticed the work of a man long since dead.

A voice behind him advised, “You may go in now.” Not you can go in now, but you may. He turned and the Inner Secretary was in the wall, a strange light in her eyes, a peculiar twist to her lips. Rueful, mocking.

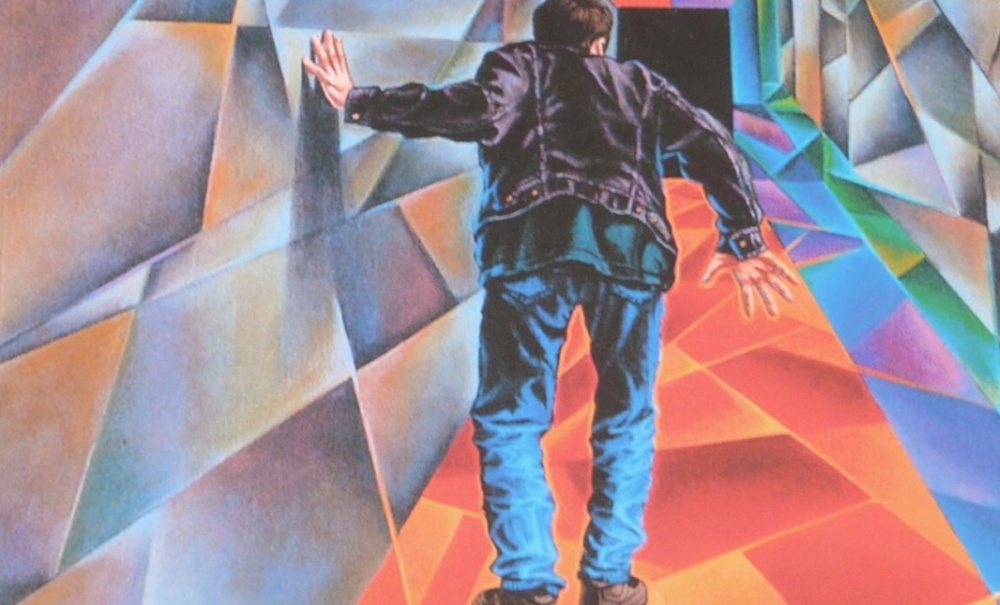

The iris he had not known was there, in the wall opposite, swirled open, and he stepped through, into a corridor of plasteel walls, subdued in lighting, painted in a way that could not hope to conceal the granite-like material of which the walls were made. Lederman wanted it known he was protected, by wealth, by position, by power and by plasteel.

“And I’m as hard as these walls,” Emory murmured, too soft for a pickup mike to relay it. But he knew he was not what he proclaimed himself to be, and he knew his words were hollow as his life had become. “But I will be, if I have to,” he added, again whisperingly.

The corridor took a sharp right turn, a sharp left, a series of dips, rises and angle turns, and he looked behind himself, just in time to see the walls slide silently into new positions; a Minotaur’s maze, guaranteed to confuse anyone who wanted out when Lederman did not wish him out.

He shrugged. After it was over, they’d come to get him anyhow. He wasn’t going to run. All he wanted was that moment, and then he was done. He had taken the turn and there was no re-turning.

Abruptly, the corridor ended, and he found himself at a featureless, blank, unpainted plasteel wall.

The wall slid into a niche, smoothly, silently, and he was a foot from the threshold to Lederman’s inner office. He had never had occasion to appear here before; if he had seen Lederman in the past, it had been over the vid. Now he was in the presence, and it disturbed him: would a man take such elaborate pains to protect himself, and then admit just anyone?

But then, Emory decided, he wasn’t just anyone.

His eyes adjusted from the soft light of the corridor into the glaring brightness of the office, and all at once he saw it, in that dream, as he had seen it that evening. Years before.

The floor was covered with a pile twist rug of crimson, that meshed with the charcoal of the walls in a way that was not flashy in the slightest. The lighting fixtures were hidden in moldings around the walls and at the baseboards. One wall was apparently a swingaround, was half open; and on its inward-turning face Emory saw a bar, a huge bookshelf and a monorail ladder to reach the upper shelves; a pneumorest chair with a decadent massage and sex-lotion attachment; a floor-model filing cabinet with vocorder pipe attached; and a Chef, its robot dials glowing in the dimness of the alcove.

The rest of the room was bare. Not a painting, or a chair, or an ash incinerator, or anything else, just Lederman’s desk.

It was half moon shaped, with a front that was stained to complement the rug and walls. On the top of the desk was a scripto, a vid box of the smallest sort, a hush-alcove into which Lederman could thrust his face when he wanted to speak privately, should someone else be in the office, and a rip handgun.

They took up very little space on the wide expanse of hardwood. And behind that desk, staring coolly at the man who had just entered, was Paul Lederman.

He had changed. It was startling, he had changed so subtly, yet completely. When last Emory had seen him, Paul Lederman had been the hail-fellow-well-met. He had had the eye-twinkle and ready-honest grin of the eternal sophomore. But that had been when Lederman, Sr., had been alive, and Paul had been heir apparent. Now, he ruled the vast Lederman Intergalactic empire; and he no longer needed the carefully contrived mementos of friendliness and sincerity. Now he was Lederman of Lederman Intergalactic. Power! And he ruthlessly used a thumb he never hesitated to grind down: for those people who required the discarded boyish grin and hearty back-slap.

His face was long, and the cheek hollows dark with a patina of stubble he would never be able to depilate completely.

As though to complement the two dark areas of his cheeks, his eyes were set deep and black under heavy brows, giving him the look of a Man. Not a man, but a Man…a man’s man, who could never be mistaken for anything else.

His hair had thinned down across the temples and now he wore it slicked straight back, no nonsense. The wave was gone. His mouth was different, too. It had held ready words of pleasure, and smiles. Now, this mouth, the one he now wore, could hold nothing but commands, and iron ingots, and foods that had not been fried.

Lederman had changed, and though he did not know it, his altered appearance had made it easier for Emory to do what he had to do.

“Hello, Cal. It’s been some time. How are you?”

Emory advanced three steps.

“That’s far enough, Cal,” Lederman stopped him by tone and a movement toward the ripper on the desk, close to his fingertips. “Now. How are you?”

Emory did not hear him.

“I just came from Dorothy,” Emory said, levelly.

Lederman’s face changed, shadowed, as though a new reason for of Emory’s appearance, had come to him. He sat back in his solid chair.

“Oh? And?”

“And she didn’t look good.”

Lederman pursed his thin lips, nodded to no one but himself. “I see. How, uh, how are you, Cal? I hear you’ve found some excellent cobalt veins out on…what was the name of that little planet…?”

“She looked terrible, Lederman. She looked—”

“—oh yes, I believe the survey called it Trigga. I always liked names that didn’t tax the tongue. Those glottal—”

“She looked dead, Lederman! She looked like you’d killed her!”

“You’re shouting, Cal.”

“Why you sonofabitch you!”

“I said that was far enough, Cal…now stop back there.”

The ripper was up, and pointed directly at Emory’s face. Cal Emory felt a chill spin down through his body, and he stopped. He wanted to move, he wanted to go forward, to put his hands around Lederman’s neck and crush the thumbs in till something oozed. He wanted to do it, but he stopped at the sight of the weapon.

Coward! He had no courage, no drive when he needed it. The loathsome realization cracked through his hatred again. He stood naked before it, knowing it was so, and knowing it would never change. His breath caught, sob-like, in his throat.

“That’s better. You always were—”

He let the sentence trail off. Emory had not needed him to complete it, having passed over it in detail a thousand times before.

“Now. What can I do for you, Emory?” The first name stage was gone. Even politeness distressed Lederman now.

“I—I—why did you do it to her?” Emory found himself pleading for a reason, for some logic, for some answer.

“No great loss.” Lederman tossed it off. He laid the ripper down, right close by his hand. No fool, he.

Emory could not believe he had heard correctly. “No…no great loss? Are you, what are you, then why did you marry her? You could have had her, why did you have to marry her…if you didn’t…why?”

“Because she wore blue, Emory. That’s why.”

Silence. While Emory’s mind threatened to snap. To accept in his own mind that he would rather have had her soiled, than not at all. To admit to himself he would not have cared if another man had made love to her, just so he might have her later, these were hard enough to reconcile. But instead of a logical reason, instead of a sane and rational answer to that hardest question, he received…what?

“I—I don’t under—”

“She wore blue, Emory. You remember that. She used to wear it all the time. I was always queer for blue, for women in blue.”

“And that…that was why you married her!?”

“You wouldn’t understand.”

“What are you talking about, you bastard! What are you saying? Are you telling me—me?—that you married Dorothy because she wore blue, for no other reason? Is that what you want me to believe, you stinking—”

Lederman’s voice cut through with softness as calm as a quicksand bog: “It doesn’t matter what you think. It never did. I’ve done what I’ve done because I had the right to do it.”

“Right? What right?”

“My right!”

Emory wanted to charge forward, to throw himself on Lederman. “Your right! Who the hell do you think you are…god?”

Lederman’s laugh was short, harsh, and ugly.

“You’re insane,” Emory breathed.

Lederman spun in the chair, and his feet hit the rug with a muffled whump. “Don’t be melodramatic. I’m as sane as you, Emory. Though right now that’s no recommendation.”

“What kind of man are you?” Loathing and disgust rang.

Lederman put his palms flat on the desk top, and leaned across at Emory, still halfway across the room. Emory had not moved since he had received the command not to do so. “What kind of a man am I? I’ll tell you, ex-roommate, because you never knew, and you’ll never know!

“I’m the kind of man who can do anything. I can do anything because I have no compunctions about who I smash, or what I smash. I count, Emory. I count above all else. It’s a world that wants to bite you, and if you let them, they’ll eat you alive.

“I eat, too, Emory. I eat better and faster, and swallow a lot more smoothly than any of them. Because I know what counts. Me!”

The word hit Emory like a pile-driver: amoral.

Lederman had no morals, no feelings, no humanity in him that a normal man could identify with. Lederman was something alien, something unhuman. Amorality was his cloak, his shield, his sword and his escutcheon. And it was so black, nothing, absolutely nothing, could soil it.

“You never understood that, did you, Emory?

“You never knew that I married her because you wanted her, and because she was wanted, I wanted her. I had her because if I had not, it would have meant I had failed. I don’t fail, Emory. That’s why I’m here, and you…you’re there!

“You’ve probably guessed by now, I was the one who engineered your expulsion from college, and for an equally good reason. I wanted you near me, to work for me, so you could see me, see how I did things, and so it would eat you the way I wanted it to.

“I wanted you as a reminder of what I’d be if I ever let myself get soft and weak and sniveling like you. You’ve done wonders for me, boy. Just wonders. I look at you in the survey records and I say, ‘That’s Cal Emory. He just ain’t got it.’ And then I look at myself and I say, ‘Keep eating, Paul. Just keep eating.’”

Emory could contain himself no longer. It was as though Lederman had gathered unto himself all the filth and madness of the universe, and was pouring it, gallon by gallon, into Emory’s bloodstream.

Cal Emory had leaped, then. He had jumped forward, and watched—as though through a mist—as Lederman remained stock still behind the desk. He had thought the man would go for the ripper at once, but Lederman did not move. Cal plunged madly forward, his hands hooked and outstretched to rip out Lederman’s tongue—

—until he cracked face first into the force screen!

He went crashing forward, his entire body coming against it with such force he thought he had broken his nose, smashed his rib cage. He felt the pain course through him, and then he was lying on his back, and the ceiling was pumping up and down like an oil derrick on some small asteroid. He felt his face with a stranger’s hand, and it was as though he had died and was resurrected.

“You mite!” Lederman was chortling softly. “Did you think for an instant I’d allow a scum like you to come in here without myself being protected? You’ve been followed all day. I knew where you went. I knew you’d been to see her. Why do you think I let you in here?

“To gloat over your ignorance, little man. To tell you what a useless, cowardly little bug you really are! Now get out of here. Get out and thank god I don’t fire you, and have you blackballed.

“I want you around for a while yet, Emory. I want you around, knowing that I can cut off your life and your job and anything else I desire, at any time. Now get out of here and stop bothering me!”

He bent, spoke into the hush alcove, and a second later a burly man in a too-tight raglan chiton came out of another doorway, on Emory’s side of the force barrier. The man lifted Emory by the scruff of the neck, and half-carried him—pain and all—out of the office, through the corridor, or one like it, out another exit, and onto the roof pad. The burly man pitched Emory from him, sending the smaller man skidding onto his side on the plasteel pad.

“Mr. Lederman don’t like wise guys,” he chimed, thinking himself voluble and clever. “Go ’way an’ don’t come back!”

Then he was gone, and Emory lay with his raw, aching cheek plastered to the night-cool plasteel.

It was out in the open now.

It would not be simple. Lederman would not be taken easily. But that didn’t matter. He had time. All his lifetime to do it. One day he would be alone with Paul Lederman and the other man would have no force barrier to protect him.

No dream to protect him now… Nothing but the sound. That special sound: the scythe.

Brutus was still silent and cold. Emory lay back against the rock, and slid his finger along the closed length of the lektroknife. It would be soon now. One way or the other. Time was short.

He was crying, and there were many reasons for it.