One of these days, as I’ve been saying for the last year or two, I’m going to pick up my ass and move to Scotland. My friends refuse to accept the statement at face value. They live in a universe where the natural forces don’t change. It has held me in it, since the dawn of memory, and they seem unable to conceive of it without me. They are wrong. I will go. And soon.

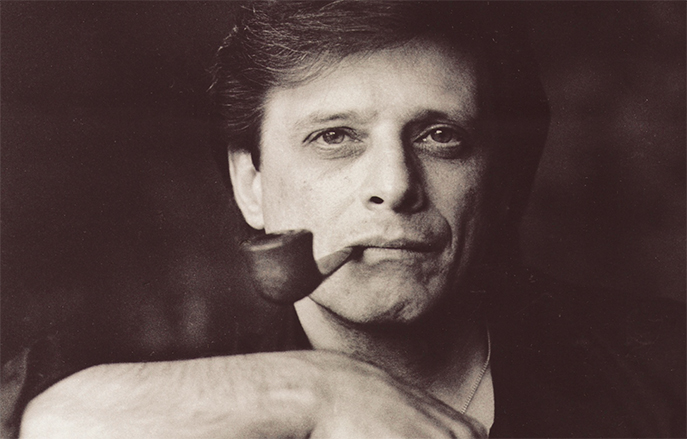

Don’t ask why Scotland, I can’t give you rational answers. I know Ireland will admit me, as a writer, free of taxes, and that is a situation greatly to be admired, but something in my blood and bones draws me to Scotland. I’ve never been there, but I’ve read about it, and it sounds like precisely what I’m looking for: a country of the mind that is quiet, far, free of complications, chill and distant. In my fantasy-eye I see myself sitting before a fireplace, smoking my pipe and reading one of the millions of books I’ve never had the time to read. In that wonderful eye I’m wearing a turtleneck sweater and there’s a shaggy dog lying somewhere nearby. Of late, sadly, since the death of my dog Ahbhu, the vision grows misty at that part. Maybe I won’t have a dog. But it’s Scotland, I’m in no doubt about that. Somewhere far North, near the Lochs, where no one will erect a missile base, or carve out a freeway; somewhere devoid of McDonald’s greaseburgers and lacquered ladies; somewhere out of touch where phones won’t ring with offers I can’t refuse; a place where letters will be slow in arriving, bearing their nickel-and-dime messages of involvement and emotional need (see last week’s diatribe in this space); a place where I can sit at my typewriter and put down all the stories that movies and television prevent me from writing now.

Dreams. How we live in them. How they make the days of keeping appointments and spending time in the company of people who say things we’ve heard in just those same words a thousand times … just a little more bearable. Without them, what an utter desolation of predictability and frustration. Even for the best of us. Even for the most unstructured of us, the freest of us. Dreams. Without them, the suicide statistics would be catastrophic.

And yet, the best dreams of all are not the ones we carry with us for years or the ones we realize or the ones we never turn into reality. The best dreams are the ones that come upon us suddenly, startling us like fauns in a forest. The ones we never knew we had, till we were living them.

I’ll tell you one that happened to me.

Despite my hunger to live in Scotland, I’m not much of a world traveler. I’ve been all over the United States, god knows, but I’ve never been to Europe. The farthest I’ve been is to Brazil.

In 1969 I was invited—along with such luminaries as Roger Corman, Josef von Sternberg, Roman Polanski, Diane Varsi plus a gaggle of science fiction writers including Heinlein, Bester, Harrison, Sheckley, Van Vogt and Farmer—to be a guest of the 2nd International Film Festival of Rio de Janeiro. In company with a redheaded screenwriter named Leigh Chapman, I made the trip, and was rather thoroughly depressed. The gap between wealthy and poor in Brazil is even more marked and cataclysmic than here in the States. I’ve written about it elsewhere, and it has nothing to do with the dream that came to me while in Rio. But it was the overlying patina of awfulness that marked the journey.

The dream came to me in this way:

As “notables,” we received invitations to endless embassy receptions. Rio went bananas over the film/sf folk. Everywhere we went, we were cheered as though we had somehow contributed to the advancement of Western Society, when, in point of fact, we were only a divertissement for the Leblon billionaires; the twentieth-century version of bread and circuses.

After the first couple such social orgies, staged with incredible opulence in settings of art and grandeur (and so painful to me personally, when matched against the sights that had been burned into my mind: the peons, in their hillside favellas, feeding a dozen family members, children, animals, from one big kettle in the front “yard” of their tin-roofed hovels … going without food so they could buy candles to burn on the steps of the glorious Catholic churches … the women wearing themselves down working in the factories so their shark-thin young men could hustle wealthy American and German widows on the Copacabana beach), I could attend no others.

Yet my hideous sense of gallows humor urged me to make one special reception. We received an invitation to the Polish Embassy’s shindig.

I confess to an ugliness of nature that demanded I see what the Polish Embassy was like.

We were advised it was black tie, and that we should be assembled in front of our hotel at 5:00 to be transported by limousines. It was 120° in Rio that summer, and even the air conditioning in the hotel was gasping. So at quarter to five we found ourselves decked out in elegance, standing on the restaurant patio, waiting for the limousines that were promised.