Harlan Ellison and I have almost nothing in common.

Harlan is Jewish and loves to bargain, to hondle, to drive sales managers almost to the verge of suicide in the course of seeking the best possible deal.

I am Gentile, and cannot bargain my way out of a paper sack. (For which see my forthcoming short story, “I Have No Jews, and I Must Buy Retail.”)

I am tall.

Harlan is…not as tall.

(At a PEN International fundraiser a few years ago, we approached Ed Asner only to have him break into laughter at the sight. He explained that side by side, we looked like the New York World’s Fair Perisphere and Trylon.)

Harlan comes from Cleveland. I hail from New Jersey.

I have multiple degrees from San Diego State University.

Harlan was booted out of Ohio State University with the lowest gpa in history, by record.

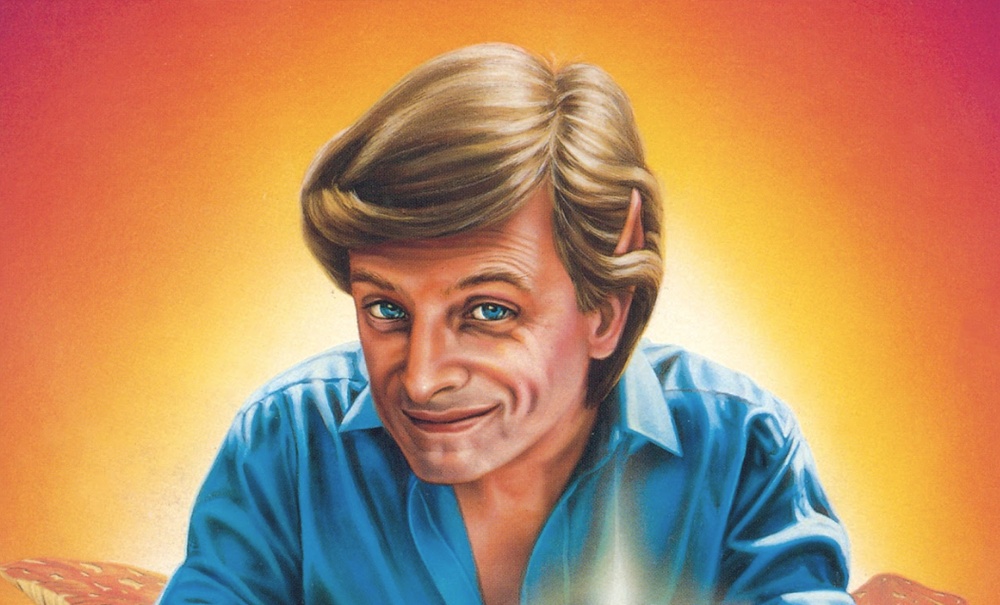

At 80, Harlan still has all of his hair.

At 60, I…well, let’s just say that I’m always the first one in a crowd to know when it’s raining. But then, I stand considerably closer to the sky.

I could continue the analysis, but by now sufficient proof has been entered in to the record to confirm the thesis noted at the beginning of this essay: that Harlan and I have almost nothing in common.

Almost.

Where we are united at the metaphorical hip, like a latter day incarnation of the Siamese twins Chang and Eng, is in our love of writing, and the impact on my life of his many essays on the craft of writing.

Understand: I would not be writing this appreciation if not for the works of Harlan Ellison. I would never have made it this far as a writer. No guff.

Yeah, yeah, I know he’s won a googleplex of awards for his fiction…enough Hugos, Nebulas (Nebulæ?), MWA and WGA awards (among others) to sink the Bismark all over again, but everyone knows they’re terrific, splendiferous, amazing, guaranteed to cure the common cold and get you laid within an hour of reading them (no Viagra needed, thank you very much, the story will do all that for you)…we all know that. So I want to talk about his introductions, the deeply personal wrap-arounds that Harlan has for decades grafted into his collections.

I not only learned how to write from those essays, I learned what it was to be a writer. I learned that writing is a holy chore. That the second you compromise you’re dead. That writing is a job of work no less than being a carpenter and thus deserving of the same professional treatment. That writing is an arena in which the strong are encouraged and the weak are devoured, not to be entered into by dilettantes, tourists, studio execs or the faint of heart.

I learned that it didn’t matter where you came from, or what school you did or didn’t attend, whether you were poor or well-off, whether or not you had contacts in the business, whether you were from the streets or uptown. The only thing that mattered was the writing, the ideas, the words.

As a kid who came from the streets, from a poor background, where guys like me were considered “dead-enders”…a kid with dreams of becoming a writer despite all these things…Harlan’s essays were a lifeboat in a sea of doubt, self-inflicted and otherwise. From my first exposure to his work in a Belmont paperback that I shoplifted from a liquor store in 1970 (Over the Edge), I starter seeking out everything he had written to that point, devouring the essays first then reading the stories.

As someone who came from the inner city streets of Newark and Paterson, burning with the desire to write something important, just as Harlan had come through the mean streets of Red Hook, and burned with even greater fury, there were days when it felt almost as though he were writing those essays directly to me.

(But then, I turn on the television every day convinced that the Russians are secretly beaming transmissions into my brain, so what the hell do I know, Comrade?)

Through the days when the obstacles seemed too great to be overcome…days when I doubted, when the words failed, when everyone around me said I didn’t have a chance…his essays were the only things that sustained me, that lit a path through the darkness, that whispered Don’t let them scare you, kid, get ill there, keep fighting, keep writing, the craft is too important to leave to the Visigoths. Don’t be afraid, there’s nothing they can do to you.

I would re-read those essays over and over until I could nearly recite them verbatim. They taught me to dream big…because after all, where is it written that our dreams should be small?

But here’s the kicker.

I’m not the only one. I cannot tell you the sheer number of other people who have told me that they were inspired, and encouraged to become writers because of those essays.

For all the crap that some people give Harlan—and believe me, the pile of poo is nearly cyclopean by now—if you push those responsible, even they will reveal that his essays had the same effect on most of them. Where they go wrong is by interpreting those essays as exercises in ego or narcissism. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

See, I know the guy…through chance and circumstance he has become my best friend…and I know why he does it.

The real reason. The secret reason. The reason even he won’t tell you, because I’m not sure he recognizes it himself.

And it is this.

He loves you.

He wants you to strive for better than you or your parents or your teachers think you deserve. He wants you to run faster, dream bigger, write better…to refuse to accept mediocrity in yourselves or in others, to punish mendacity and reward charity, to dismiss cupidity and encourage intelligence, to forge a more perfect union, to be kind to one another.

When he yells, what you are hearing is the anger of someone who cannot understand why his lover remains in self-inflicted agony…why we do the terrible things we do so often and so easily to one another…and who knows that if the argument designed to make things better is to continue, as it must, then he must commit himself to shouting forever at the top of his lungs, even if doing so means standing alone in his cause.

Why is Harlan so beloved by some, so viciously attacked by others, and so misunderstood by most?

Because Harlan is his writing, he is his books, and as Georg Christoph Lichtenberg once noted, “A book is like a mirror: If an ass peers in, you can’t expect an apostle to peer out.”

And I, for one, am happy to see his presence and his work recognized by you a happy conclave of apostles.

He deserves it.

And so do you.

So just freaking deal with it, okay?

Michael Straczynski

Los Angeles, California