A bird does not sing because it has an answer.

It sings because it has a song.

Chinese Proverb

Three Explicit Essays in Language

So Direct Even You Can Understand,

on the Subject of Producing Some Kick-Ass Fiction!

A note from the author to the reader: André Gide once wrote, “Everything’s already been said, but since nobody was listening, we have to start again.” I have been a professional writer for now fifty years. On and off, I have taught writing in a thousand various venues for at least thirty-five of those years. Helped create the Clarion Workshops with Robin Scott Wilson. Have “discovered” and helped nurture the art and craft of perhaps a hundred men and women who now make their living, either in full, or in significant measure, by way of the written word. There are not merely hundreds of good books on “how to write,” there are assuredly thousands. And yet, when one reads the Slush Pile, or the unsolicited stories that keep coming unwanted and unannounced, when one reads the spavined and crippled efforts that glut the small press publications, one sadly understands the wearying truth of Gide’s observation. The three essays presented here were written in 1977 and were originally published in a marvelous semi-pro magazine called Unearth. They have been reprinted here—you’ll excuse the dated references and substitute your own current ones—because, well, everything’s already been said, you’ve been told all this in a thousand books, but since nobody was listening, well, once more into the breach, dear friends. And remember: “momentarily” ain’t the same as “in a moment”; and every time you say “like,” as in “I like went to see her in like her house, y’know,” the Devil swallows a bite of your immortal, ungrammatical soul.

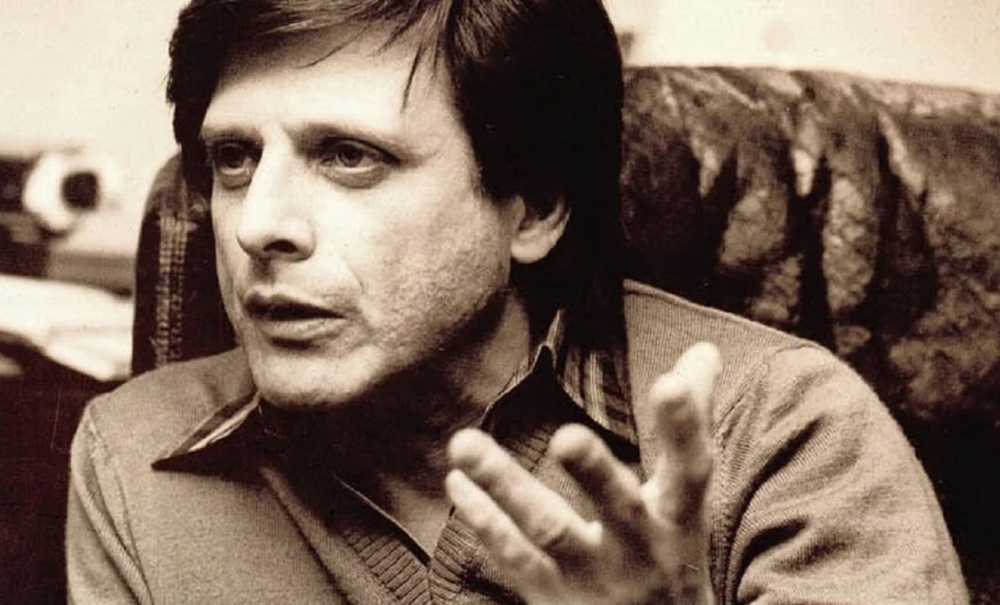

Harlan Ellison

11 February

Year 2000

1. First, There Was the Title

Unearth / Summer 1977

Like most comfortable, familiar old-shoe clichés, there is an important and irrefutable kernel of truth in this one: people, schmucks though they may be for doing it, do judge a book by its cover. Even I do it once in a while. I bought a recent Bantam paperback, Apeland, because of the cover. There was a mystery novel I spent seven dollars to purchase, in hardcover, because of the cleverness of the cover art. It was called Dead Piano. It wasn’t that good a novel, but what did the author or the publisher care by that time…they had me. Not to mention my seven dollars.

And after judging by the cover, readers judge by the title. Many times they read the back spine of the book, or the title on a table of contents if it’s a shorter story in question, so it’s judged before the cover. What you call a story is important.

I’ll try to tell you why. And how to do it well.

Here’s a sample group of titles. I’ve made them up on the moment. Say they’re arrayed on a contents page, each bylined with a name you don’t know, so you have no preference based on familiarity with an author’s previous work. Which one do you read first?

The Box

Heat Lightning

Pay as You Go

Hear the Whisper of the World

The Journey

Dead by Morning

Every Day Is Doomsday

Doing It

Now, unless you’re more peculiar than the people on whom I tried that list, you picked “Hear the Whisper of the World” first, you probably picked “Doing It” next, and “Dead by Morning” third. Unless you’ve led a very dull life, you picked “The Box” next to last, and would read everything else before selecting “The Journey.” If you picked “The Journey” first, go get a bricklayer’s ticket, because you’ll never be a writer. “The Journey” is the dullest title I could think of, and believe me I worked at it.

It wasn’t the length or complexity of “Hear the Whisper of the World” that made it most intriguing. I’ll agree it may not even be the most exhilarating title ever devised, but it has some of the elements that make a title intriguing, that suggest a quality that will engender trust in the author. He or she knows how to use words. S/he has a thought there, an implied theme, a point to which the subtext of the story will speak. All this, on a very subliminal level as far as a potential reader is concerned. And (how many times, to the brink of exhaustion, must we repeat this!?) trust is the first, the best thing you can instill in a reader. If readers trust you, they will go with you in terms of the willing suspension of disbelief that is necessary in any kind of fiction, but is absolutely mandatory for fantasy or science fiction.

The second thing it possesses is a quality of maintaining a tension between not telling too little and not telling too much. Remember how many times you were pissed off when a magazine editor changed a title so the punch line was revealed too early: you were reading along, being nicely led from plot-point to plot-point, having the complexity of the story unsnarl itself logically, and you were trying to outguess the writer, and then, too soon, you got to a place where you remembered the title and thought, oh shit, so that’s what it means! And the rest of the story was predictable. The title stole a joy from you.

So a title should titillate, inveigle you, tease and bemuse you…but not confuse you or spill the beans. Titles in the vein of “The Journey” neither excite nor inform. “Hear the Whisper of the World,” I hope and pray (otherwise it’s a dumb example), fulfills the criteria.

The Blank of Blank titles are the kinds of titles away from which to stay, as Churchill might have syntactically put it. You know the kind I mean: The Doomfarers of Coramonde, The Dancers of Noyo, The Hero of Downways, The Ships of Durostorum, The Clocks of Iraz. That kind of baroque thing.

Naturally, I’ve picked examples of such titles that include another sophomoric titling flaw. The use of alien-sounding words that cannot be readily pronounced or—more important—when the reader is asking to purchase the book or recommending it to someone else, words that cannot be remembered. “Hey, I read a great book yesterday. You really ought to get it. It’s called the something of something…The Reelers of Skooth or The Ravers of Seeth or…I dunno, you look for it; it has a green cover…”

Asimov believed in short titles, because they’re easy to remember by sales clerks, bookbuyers for the chain stores, and readers who not only don’t recall the titles of what they’ve read, but seldom know the name of the author. On the other hand, both Chip Delany and I think that a cleverly constructed long title plants sufficient key words in a reader’s mind that, even if it’s delivered incorrectly, enough remains to make the point. Witness as examples, “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones,” “The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World,” “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman,” or “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth.” There is strong argument both ways. “Nightfall,” Slan, Dune, and “Killdozer” simply cannot be ignored. But then, neither can Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

The rule of thumb, of course, is simply: if it’s clever and catchy enough, short or long doesn’t make a bit of difference.

But try to avoid being too clever. You can bad-pun and out-clever yourself into annoying a reader before the story is ever considered. I Never Promised You a Rose Garden makes it, but Your Erroneous Zones simply sucks. The original title for Roger Zelazny’s “He Who Shapes,” published in book form as The Dream Master, was “The Ides of Octember,” which seems to me too precious by half, while the title Joe Haldeman originally wanted to put on his Star Trek novelization—Spock, Meshuginah!—caroms off into ludicrousness. But funny. I know from funny, and that is funny. Thomas Disch is a master at walking that line. Getting into Death is masterful, as is Fun with Your New Head. But the classic example of tightropewalking by Disch was the original title of his novel Mankind Under the Leash (the Ace paperback title, and a dumb thing it is), which was originally called The Puppies of Terra. (That’s its title in England.)

Arthur Byron Cover has a flair for the utterly ridiculous that is so looney you have to buy the book to see if he can pull it off. Witness: The Platypus of Doom.

Until the very last tick before production, the title of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind was Mules in Horses’ Harness; and though I truly love the hell out of it, sufficiently to have appropriated it half-a-century later for an essay I wrote, I think Scott Fitzgerald was well-pressured when his publisher badgered him into retitling Trimalchio in West Egg as The Great Gatsby.

The name of a character, if interesting, can be a way out when you’re stuck for a title. It’s surprising how few sf novels have done this, indicating the low esteem most traditional sf writers have placed on characterization, preferring to deal with Analog-style technician terms such as “Test Stand,” “Flashpoint,” “Test to Destruction,” or “No Connections.” We have so few novels with titles like The Great Gatsby, Babbitt, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or Lord Jim. Delany scored with Dhalgren, I’ve had some success with “Knox,” and Gordon Dickson’s best-loved story is “Black Charlie.”

Ideally, a title should add an extra fillip when you’ve finished reading a story. It should capsulize it, state the theme, and make a point after touchdown. It should, one hopes, explain more than you cared to state baldly in the text. Judith Merril’s “That Only a Mother” is a perfect example, as is the double-entendre of her “Dead Center.” It is an extra gift to the alert reader, and makes the reader feel close to you.

By the same token, you dare not cheat a reader with a clever title that doesn’t pay off. The one that pops to mind first is “The Gun Without a Bang,” one of the best titles from the usually satisfying Robert Sheckley. Great title. The only thorn on that rose was that it was a dumb story about some people who find a gun that didn’t make any noise, which says a whole lot less than the symbolic, metaphysical, textual, or tonal implications passim the title’s promise.

One of the most brilliant title-creators sf has ever known is Jack Chalker. I’m not talking about the actual stories, just the titles. Beauties like Midnight at the Well of Souls, and The Devil Will Drag You Under, Pirates of the Thunder, and “Forty Days and Nights in the Wilderness” are to die for.

But when—way back in 1978—Jack saw publication of a short story with the absolute killer title “Dance Band on the Titanic,” everybody wanted to assassinate him. First, because the title was utterly dynamite; and second, because the stupid story was about the dance band on the Titanic!

No! we screamed at him, you great banana, you don’t waste a prime candidate for beautiful allegory on a story that is about the very thing named in the title. Man was lucky to escape with his life!

For myself, I cannot begin a story until I have a title. Sometimes I have titles—such as “The Deathbird” or “Mefisto in Onyx”—years before I have a story to fit. Often a story will be titled in my mind, be the impetus for writing that particular piece, and then, when I’ve finished, the title no longer resonates properly. It is a title that has not grown to keep pace with more important things in the story, or the focus was wrong, or it was too frivolous for what turned out to be a more serious piece of work. In that case, painful as it may be to disrespect the spark that gave birth to the work, one must be bloody ruthless and scribble the title down for later use, or jettison it completely. That is the mature act of censorship a writer brings to every word of a story, because in a very personal way that is what writing is all about: self-censorship. Picking “the” instead of “a” means you not only exclude “the,” but all the possible storylines proceeding from that word. You kill entire universes with every word-choice. And while it’s auctorial censorship, it is a cathexian process forever separating the amateurs from the professionals.

I cannot stress enough the importance of an intriguing and original title. It is what an editor sees first, and what draws that worthy person into reading the first page of the story.

No one could avoid reading a story called “The Hurkle Is a Happy Beast” or “If You Was a Moklin,” but it takes a masochist to plunge into a manuscript titled “The Wicker Chair.”

I leave you with these thoughts.

Right now I have to write a story called “The Other Eye of Polyphemus.”